Rising domestic inflation led to the establishment of the Prices and Incomes Commission in 1968 and to the introduction of a restrictive s...

Rising domestic inflation led to the establishment of the Prices and Incomes Commission in 1968 and to the introduction of a restrictive stance on monetary policy. This occurred at a time when the United States was pursuing expansionary policies associated with the Vietnam War and with a major domestic program of social spending. Higher commodity prices and strong external demand for Canadian exports of raw materials and automobiles led to a sharp swing in Canada’s current account balance, from a sizable deficit in 1969 to a large surplus. Combined with sizable capital inflows associated with relatively more attractive Canadian interest rates, this put upward pressure on the Canadian dollar and on Canada’s international reserves.

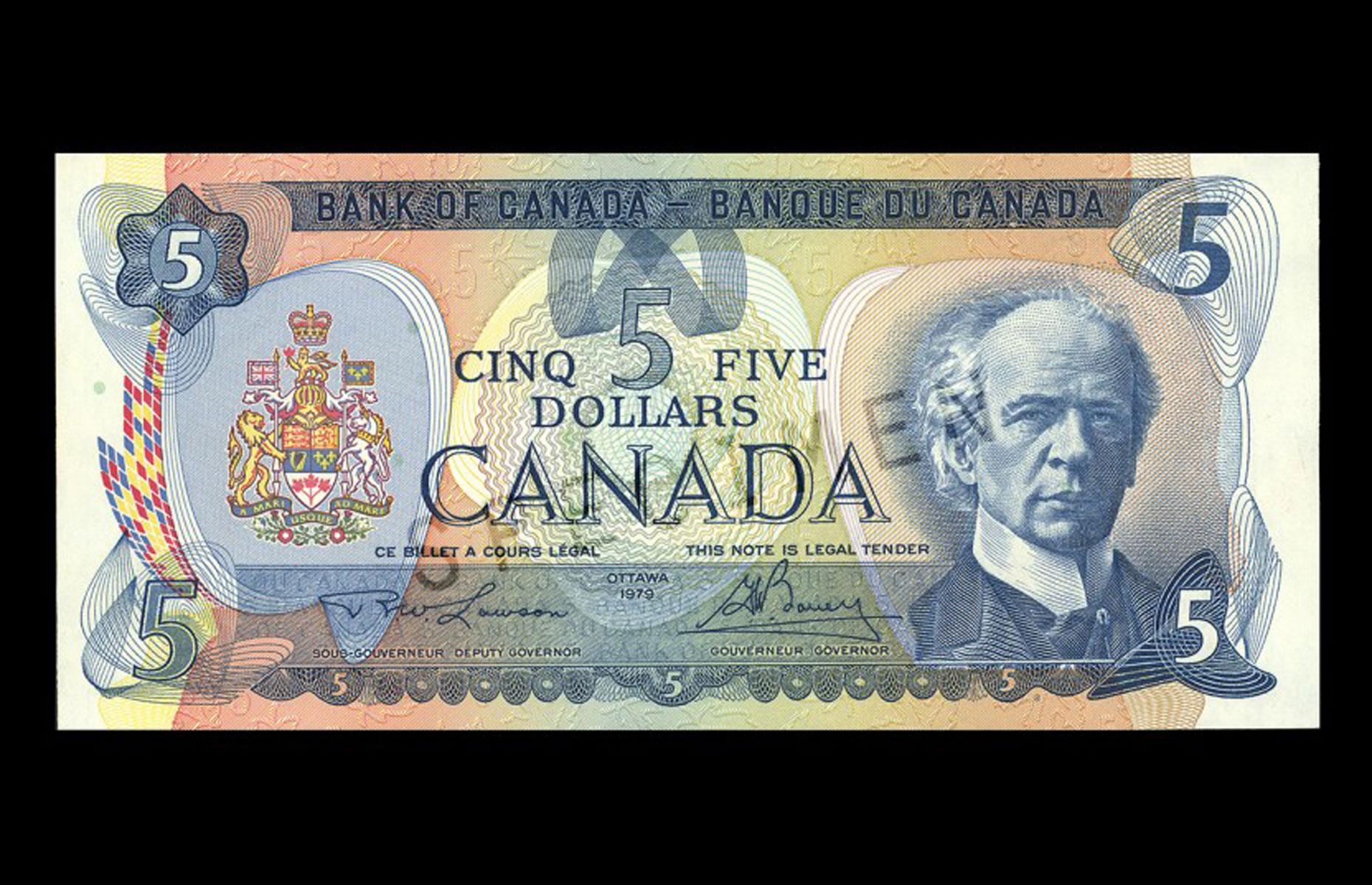

The resulting inflow of foreign exchange led to concerns that the government’s anti-inflationary stance might be compromised unless action was taken to adjust the value of the Canadian dollar upwards.90 There was also concern that rising foreign exchange reserves would lead to expectations of a currency revaluation, thereby encouraging speculative short-term inflows into Canada. On 31 May 1970, Finance Minister Edgar Benson announced that for the time being, the Canadian Exchange Fund will cease purchasing sufficient U.S. dollars to keep the exchange rate of the Canadian dollar in the market from exceeding its par value of 92½ U.S. cents by more than one per cent (Department of Finance 1970). Bank of Canada $50, 1975 series This note was part of the fourth series issued by the Bank of Canada. This multicoloured series incorporated new features to discourage counterfeiting. While Canadian scenes still appeared on the backs (this note shows the “Dome” formation of the RCMP Musical Ride), there was more emphasis on commerce and industry. The Queen appeared on the $1, $2, and $20 notes. Others carried portraits of Canadian prime ministers. 90. Consumer prices were rising at about 4 to 5 per cent through 1969 and early 1970. Wage settlements were also rising, touching 9.1 per cent during the first quarter of 1970. 72 A History of the Canadian Dollar Canadian authorities also informed the IMF of their decision to float the Canadian dollar and of their intention to resume the fulfillment of their obligations to the Fund as soon as circumstances permitted. The Bank of Canada concurrently lowered the Bank Rate from 7.5 per cent to 7 per cent, an action aimed at making foreign borrowing less attractive to Canadian residents and at moderating the inflow of capital, which had been supporting the dollar. The government made the decision to float the Canadian dollar reluctantly. But Benson believed that there was little choice if the government was to bring inflation under control. He hoped to restore a fixed exchange rate as soon as possible but was concerned about a premature peg at a rate that could not be defended. As in 1950, other options were considered but rejected. A defence of the existing par value was untenable since it could require massive foreign exchange intervention, which would be difficult to finance without risking a monetary expansion that would exacerbate existing inflationary pressures. A new higher par value was rejected, since it might invite further upward speculative pressure, being seen by market participants as a first step rather than a once-and-for-all change. Widening the fluctuation band around the existing fixed rate from 2 per cent to 5 per cent was rejected for the same reason (Beattie 1969). The authorities also considered asking the United States to reconsider Canada’s exemption from the U.S. Interest Equalization Tax. Application of the tax to Canadian residents would have raised the cost of foreign borrowing and, hence, would have dampened capital inflows. This, too, was rejected, however, because of concerns that it would negatively affect borrowing in the United States by provincial governments (Lawson 1970a). While recognizing the need for a significant appreciation of the Canadian dollar, the Bank of Canada saw merit in establishing a new par value Image protected by copyright at US$0.95 with a wider fluctuation band of ±2 per cent (Lawson 1970b).

A new fix was seen as being more internationally acceptable than a temporary float, and since the lower intervention limit of about US$0.9325 would have been the same as the prevailing upper intervention limit, such a peg would have been accepted by academics who favoured a crawling peg. A new peg was also viewed as desirable because it would preserve an explicit government commitment to the exchange rate consistent with its obligations to the IMF. There was also some concern that a floating exchange rate might “encourage, as it had in the late 1950s, an unsatisfactory mix of financial policies” (Lawson 1970a). For its part, the IMF urged Canada to establish a new par value.

Fund management was concerned about the vagueness of Canada’s commitment to return to a fixed exchange rate, fearing that the float would become permanent as it had during the 1950s. The IMF also feared that Canada’s action would increase uncertainty within the international financial system and would have broader negative repercussions for the Bretton Woods system, which was already under considerable pressure. Canadian authorities declined to set a new fix, emphasizing the importance of retaining adequate control of domestic demand for the continuing fight against inflation.

No comments